|

|

side from the oversize

bowling balls planted between the shrubs under the front window, artist Judy

Onofrio's house in Rochester, Minn., could pass -- from the front -- as the home

of a Mayo Clinic neurosurgeon. Which it also is.

side from the oversize

bowling balls planted between the shrubs under the front window, artist Judy

Onofrio's house in Rochester, Minn., could pass -- from the front -- as the home

of a Mayo Clinic neurosurgeon. Which it also is.

Its two stories of white clapboard nestle into a well-manicured lawn on a winding street a few blocks south of the renowned medical complex where Judy's husband, Burton Onofrio, does neurosurgery. Gray shutters frame the windows and a van stands in front of the attached two-car garage: suburbia incarnate.

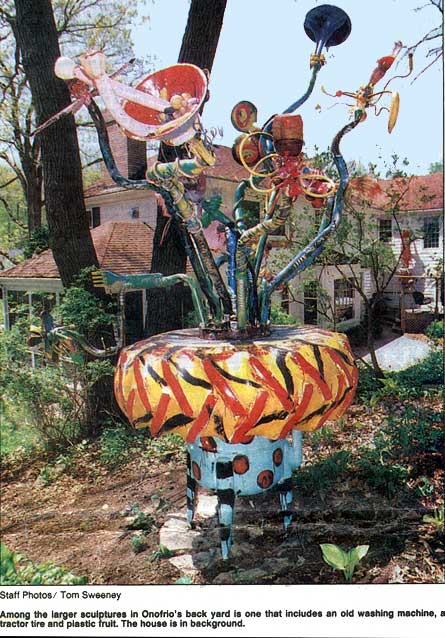

But on the terraced hillside out back, wow! Bowling-ball mania! Whirligigs galore! This is where the real Judy Onofrio blossoms amid glitter and glitz, plastic fruit and flowers, tractor tires, duck decoys. toy swords, sea horses, sailfish, glass telephone wire insulators, mirrors and terraces on which hundreds upon hundreds of Virginia bluebells flower each spring.

In Minnesota's sometimes-insular art world, there is only one artist in Rochester, maybe in the whole of Southern Minnesota. With apologies to all the rest of you out there, that one artist is Onofrio. For more than 20 years, Onofrio has been a force in the Rochester art community as ceramicist, jeweler:, teacher, guiding light and big personality.

But even world-connected Rochester couldn't contain Onofrio, whose work has, in the past three years, appeared in galleries in Kansas Philadelphia and New York turned in Ornament magazine and Showcased in the Netherlands, Finland, Sweden and a U.S. Information Agency show touring the Middle East.

Her most elaborate exhibition to date -- an extravagant gallery sized installation called "Judyland" -- is on view at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts through July4. During the next year "Judyland" also will travel to Grand Forks, ND, and St. Louis. (Watch for the "l've seen Judyland" bumper stickers.)

'She is a really important,

singular voice in contemporary art, not just in craft, but in late 20th-century

art," said Helen Drutt, an art dealer and collector who has shown Onofrio's

Work in her Philadelphia and New York galleries.

'She is a really important,

singular voice in contemporary art, not just in craft, but in late 20th-century

art," said Helen Drutt, an art dealer and collector who has shown Onofrio's

Work in her Philadelphia and New York galleries.

Drutt remembers her reaction upon first seeing Onofrio's bejeweled brooches at a jewelry show in 1989: "I saw them, and inside -- physically, spiritually and emotionally -- I screamed. That's what happens when you see work that is really fresh and unique."

The brooches -- fist-sized clusters of gilded birds, animals, beads and pop-culture geegaws -- were so unusual that a Finnish museum picked one of them for an exhibition poster, out of some 300 pieces of jewelry. The pin, which had a crocodile holding a gold bead in its mouth, "was totally alien to the whole Scandinavian sensibility," said Drutt, who helped organize the show.

Onofrio's exuberant sensibility might appear to be a little alien in Mayoland, too, but her closest neighbors insist it’s not. "Everybody should be so lucky to have neighbors like the Onofrios," said P.G. Arnold, another Mayo Clinic surgeon, whose back yard adjoins the Onofrios'.

Arnold and his wife, Susan, have lived next door for 14 years and have "always" been good friends with the Onofrios. Susan Arnold, who describes herself as "more traditional" than Judy, thinks "it's refreshing to find a person that free to express themselves in our society.

There are other advantages to having an original neighbor. "I never throw anything away," said P.G. "I take it to Judy, and she makes art out of it. Broken mirrors and bowling balls are especially good. I don -think she's ever had enough old bowling balls."

In Onofrio's garden, bowling balls sprout like beanstalks from spikes, pillars and posts. A funny thing happens to them after they're exposed to a few seasons of hard rain and winter snow: their glossy surfaces erode, revealing suede soft skin in colors of sea foam and mulled wine.

|

|

|

|

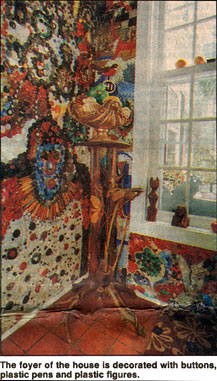

It's; Onofrio's particular talent to see such potential in stuff that other5 discard as trash. That's what lures her to garage sales and junk shops and prompts her to fill the garage with boxes and barrels of neatly sorted discards of every sort. Gallon buckets of white buttons, gallon buckets of black buttons, stacks of decorative tin religious plates, rolls of garden hose, tubs of Jell-O molds, belt buckles, pencils, candlesticks, perfume bottles.

They love me at garage sales because I take anything other people don't buy," she said. "Jell-O molds are very big. I use a lot of garden hose. It makes great vines and edges."

Although self-taught as an artist, Onofrio is not just some eccentric weirdo lost in glittery visions. Each of her elaborate constructions which range in size from shoulder-bending brooches to 8-foot-tall urns and grottos -- is built on a sturdy armature of wood or metal and assembled with a brilliant and highly refined eye for color, design and theme. Every sculpture is encrusted with thousands of buttons, beads, shells and other decorations, and every visual note is orchestrated smoothly into the larger composition.

"lt's very difficult to embellish to this extent without overwhelming the form, but her work succeeds because she maintains a very tough balance," said Laurel Reuter, founding director of the North Dakota Museum of Art in Grand Forks and author of the exhibition catalog.

The Garden of Eden as a place of innocence and desire is a recurrent theme in the museum show. ln a wall sculpture called "Temptation," a pearl-encrusted deer gazes at a beaded apple dangling from the In a neck of a snake. In a frieze titled "Call Me Anytime," a lusty bear dangling a telephone receiver is surrounded by leering faces. (She uses taxidermists' plastic-foam models as bases for her animal heads.)

"The whole thing is

about sensuality, temptation, sensual delight and the dark side of that, but it

is all done very subtly through image and metaphor, " said curator Reuter,

who has known Onofrio for 15 years.

"The whole thing is

about sensuality, temptation, sensual delight and the dark side of that, but it

is all done very subtly through image and metaphor, " said curator Reuter,

who has known Onofrio for 15 years.

Sherry Leedy, co-owner of Leedy Voulkos Gallery in Kansas City and a longtime friend of Onofrio’s, finds autobiographical footnotes in these exuberantly decorated sculptures. Paul Bunyan characters suggest Onofrio’s Minnesota ties. Buddha’s and other Asian themes recall her years in Japan, and creatures like the bear with the phone are straight portraiture.

"It’s rowdy, raucous, and has a phone hanging down, which is like Judy. She's on the phone all the time," said Leedy.

"Judyland" sums up a long and meandering career that began in earnest when Onofrio, now 53, set up her first studio in Rochester back in 1968. She and Burton already had been married for 11 years and had three children, all born before Judy was 23.

Born in 1939 in New London, Conn., Judy Onofrio grew up on the East Coast where her father, a three-star admiral, was stationed at various naval bases. She met her husband-to-be in 1956 in Sasebo, Japan, where she was visiting her parents and he was a young U.S. Navy medical officer on shore leave. They married the next summer, after she graduated at 18 from Sullins College in Virginia with a two-year degree in business law and economics.

Judy Onofrio had always been interested in an, inspired mostly by a free- spirited' aunt who built shell niches in her house, painted scenes on her furniture and had a magical garden that had enchanted Judy as a girl. In the spirit of Aunt Trude, Judy has always collected stuff -- 90s ceramics, '50s jewelry and art by eccentric visionaries. (Artist-decorated dolls made from Mrs. Butterworth syrup jars line the den shelves. "I see her [Mrs. 8] as a vehicle for self-portraiture," Onofrio explained.)

In Rochester she got involved with the local art center, serving briefly as its director, as a longtime board member and founder of the Total Arts Daycamp, a summer program the brings professional artists to town to teach kids in two-week residencies. Now nationally acclaimed, the program is 18 years old, and she's still running it.

Through friendships with sundry artists, Onofrio taught herself ceramics and showed her colorful constructions throughout the Midwest in the 1970s. She lectured, gave workshops at colleges and was founding president of the Minnesota Crafts Council.

In the 1980s, she abandoned

ceramics to build large outdoor constructions and stage events like a "fire

performance" in Grand Forks for which in 1985 for which she built -- and

torched -- a 20-foot-tall wood-and paper pyramid laced with gunpowder. With the

fire department standing by, it burned for 10 minutes and made a drawing in

light and darkness against the night sky.

In the 1980s, she abandoned

ceramics to build large outdoor constructions and stage events like a "fire

performance" in Grand Forks for which in 1985 for which she built -- and

torched -- a 20-foot-tall wood-and paper pyramid laced with gunpowder. With the

fire department standing by, it burned for 10 minutes and made a drawing in

light and darkness against the night sky.

Through all of this, Onofrio never felt constrained to follow a more conventional life, she said.

'Burton and I pretty much operate in our own worlds, l guess. I'm involved in my work, and he's involved with his work. Most of our friends are artists, and when we're off, we have a whole community of people who are interested in the things we're interested in."

Her husband had been away on business for several days, and Judy Onofrio was clearly eager for his return later that day. He's an enthusiastic gardener, cat collector (they have five) and the household's chief cook.

"Theirs are two distinct careers, but ... they're very, very close," said their friend B.J. Shigaki, director of the Rochester Art Center. "Once you get to know the both of them, it's like being open to a whole different way of life -- and not being rigid."